Authors

Partner, Corporate, Toronto

National Co-Chair, Toronto

Partner, Corporate, Toronto

Associate, Corporate, Toronto

Since the introduction of the May 2016 take-over bid amendments there has been a marked decline in the number of hostile take-over bids in Canada. The following chart sets out the number of hostile bids launched since 2005 to date:

Note: Includes all hostile bids that targeted Canadian-listed public companies from January 1, 2005, to December 16, 2024. Data prior to 2017 drawn from Kingsdale Advisors.

The precise degree to which the 2016 bid amendments have caused this precipitous decline is unclear, but the amendments have likely played a contributing role by increasing the financing costs and market risk associated with launching a bid. More specifically, the 2016 amendments included an extended minimum bid period of 105 days (versus a previous 35 days) and an extension of at least 10 days after the minimum tender condition is satisfied. Take-over bids are required to have financing in place, and lengthier bid periods result in increased financing costs. In addition, the 2016 amendments introduced a 50% mandatory minimum tender condition before any shares can be taken up. This mandatory minimum tender condition has eliminated “any and all bids”. Previously a hostile bidder could have taken up any shares tendered to the bid, provided all bid conditions were satisfied or waived. The 50% minimum tender condition has enhanced the leverage of major shareholders vis-à-vis the bidder and the target. Indeed, the Ontario Securities Commission (the Commission) noted in its reasons in the ESW/Optiva decision [PDF] that the minimum tender condition could result in bids not being made at all or shareholders being deprived of the ability to respond to a bid; the Commission observed that it materially altered the bid dynamics among the bidder, the target and control block holders.

Shareholder activism on the rise

There has been a recent increase in the number of proxy contests, as illustrated in the chart below:

Note: Data drawn from Kingsdale Advisors. Proxy contests include a shareholder: (i) making its activist intent known through a news story, press release, a 13D or an early warning report; (ii) requisitioning a shareholder meeting; (iii) announcing an intention to nominate alternate directors; (iv) soliciting alternative proxies; (v) conducting a “vote no campaign” on either a director election or a M&A transaction; or (vi) announcing an intention to launch a hostile bid. The data also includes transaction related activism and not merely proxy contests related to board composition. Finally, the data also picks up the announcement of an intention to launch a hostile bid.

The data in the chart only captures publicly disclosed instances of shareholder activism and therefore does not include “behind the scenes” instances where there may have been changes in board composition and other measures as a result of private discussions and negotiated outcomes between issuers and activist shareholders.

Activism is generally a lower cost alternative than making a bid in a battle for corporate control, since activists can gain influence and potentially board control with smaller equity stakes. The bid amendments have arguably further incentivized activism by increasing the costs and risks associated with launching a hostile bid.

Number of public companies and IPO activity on continued decline

When examining the decline in hostile bids, another factor to consider is the shrinking number of public companies. Since 2002, there has been a precipitous decline in the number of operating issuers listed on the TSX and the TSX-V as shown in the following graph:

Source: Data drawn from TSX/TSXV Market Intelligence Group as of October 31, 2024. Data only includes operating issuers and does not include exchange-traded funds and closed-end funds.

There has been a 40% decrease in the number of public operating issuers listed on the TSX since 2008 and there are 42% fewer of these issuers listed on the TSXV than in 2002. Many publicly traded issuers were delisted as a result of M&A transactions where they were taken private.

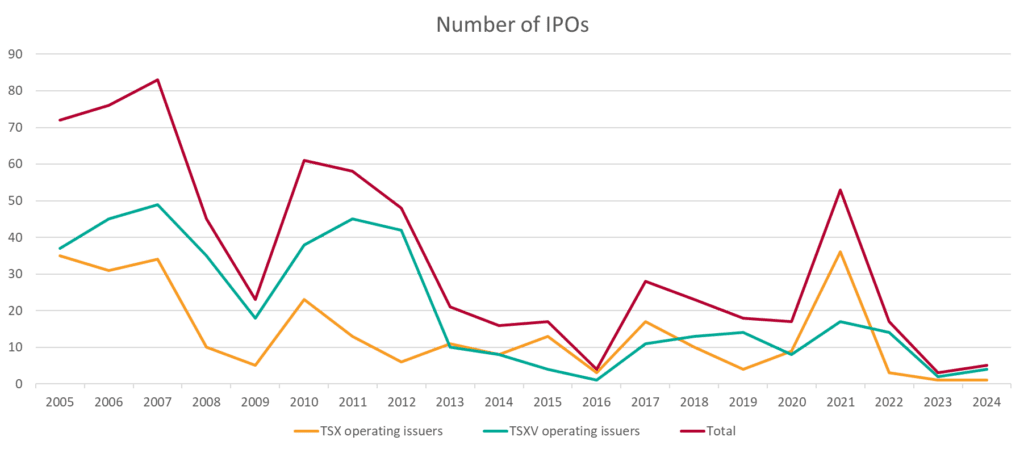

At the same time, the rate of replenishment of listed operating issuers through initial public offerings (IPOs) has recently been anemic:

Note: Data drawn from J. Ari Pandes and available TMX data sources as of December 16, 2024. Data only includes operating issuers and does not include exchange-traded funds and closed-end funds.

There have been only five IPOs of operating issuers on the TSX between January 1, 2022, and November 30, 2024: three in 2022, one in 2023, and one in 2024. Apart from a short-lived IPO boom fueled by tech companies in 2020-2021, the overall trajectory of IPOs has been decreasing.

The primary explanation for this trend is the growth in private capital markets, which are much deeper than ever before. Companies can now choose to stay private for longer and enjoy liquidity and financing options that only used to be available by going public. In doing so, they avoid facing the disclosure and governance obligations and costs of going public.

Conclusion

Since the 2016 bid amendments, there have been fewer hostile bids and an increase in shareholder activism. At the same time, the number of public companies and IPOs has continued to decline. While transaction activity is cyclical, these trends may well persist over the longer term.

Securities regulators may be satisfied with the current take-over bid regime and that it may create greater incentives than in the past to engage in activism rather than launch a hostile bid. If there is a desire to increase hostile bid activity, one potential policy change that might be considered is relaxing the 50% minimum tender condition in certain circumstances.

The declining number of public companies is a global phenomenon. While securities regulators do have tools at their disposal to reduce the cost of going public, the benefits will need to be weighed against the costs of potentially lessening investor protection. Given the depth and breadth of private capital markets, it is unclear whether changes in securities regulation alone would stem the tide. Issuers will need compelling reasons to go public rather than stay private. If having more public companies is an important policy objective, legislatures may need to get involved in devising laws and policies to achieve this end.